Pete Rose and the Limitations of Hustle

As a kid I loved baseball and Pete Rose. I still love baseball, but evidence demands a verdict, and I long ago had a reckoning over Pete Rose.

Fandom is an inherently insular thing that is specialized to the individual. Being a fan usually develops based on where you grow up, who you grow up around, and crystalized by key events witnessed, experienced, or ingrained. There was zero chance a kid like me, born to a multiple degree holder from West Virginia University and raised in a state with no professional sports team and where Mountaineer Field on gameday is the largest city in the state, was going to be anything but musket-firing Old Gold and Blue for life.

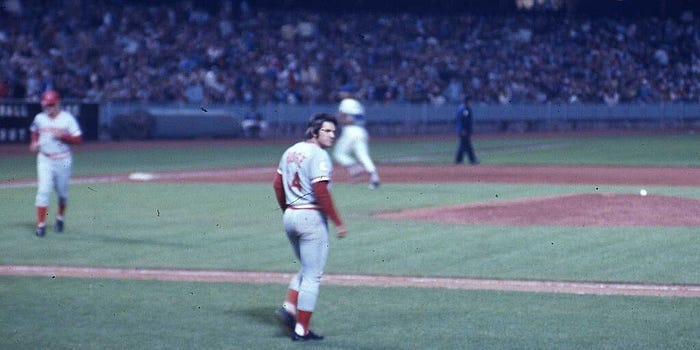

My fandom of the Cincinnati Reds baseball team is a bit more complicated. My father’s 50’s childhood and the Mickey Mantle New York Yankees being the only team to have radio coverage in West Virginia at the time lead him down that road. Outside of dad’s Bronx apostasy everyone else on both sides were Reds fans. My maternal grandfather hardwired his love of the Red from the 60s through the Big Red Machine of the 70s into the family before I arrived. Most West Virginia houses had the Appalachian trinity photo set of John F. Kennedy, John L. Lewis, and Jesus Christ up on the wall, but as far as Up Yonder baseball went Pete Rose wasn’t too far behind.

Fair to say, young Andy was born into being a Pete Rose fan. Adult Andy as well, as there are pictures of me taken all over the world wearing a Reds hat on the occasions, I’m not donning WVU gear, including on the jetway at the airport coming home from my second Iraq deployment and holding my four-month-old daughter for the first time with the red ballcap right above a rather emotional me and a perplexed looking baby girl. In short, I’ve been a Cincinnati Reds fan for all my life.

All of which meant I was just old enough to enjoy my trips to Riverfront Stadium with my father in the 1980s and 90s, vaguely aware but not understanding the hardball yin and yang of the Cincinnati Reds on-field play with the chaos of Marge Schott’s peculiarities and prejudices as an owner. Mostly being a winning team covered up and excused much of it for a while; until it couldn’t be ignored or excused.

Pete Rose found the hardline of what a legend could and couldn’t get away with pretty quick. By 1989, the allegations and investigations into Rose led to him voluntarily accepting a permanent placement on baseball’s ineligible list, mostly described since, not incorrectly, as a “lifetime ban.” For most of the rest of his life Pete Rose would oscillate between “screw you” defiance and “I didn’t think permanent meant, like…PERMANENT” mealy mouthing to try and get back in. There were moments of genuine remorse and apology alternating with moments of defiance, bombast, and resentment.

The “Charlie hustle” nickname took on a different meaning for post-ban Pete Rose as he was constantly marketing himself, selling autographs and anything else he could. His yearly capitalistic encampment outside the Baseball Hall of Fame festivities became an event unto itself. In later years, his May to August 2015 stint on Fox commentating came to an abrupt end when Rose’s admitted relationship with an underaged girl during his playing days came to light because of a defamation lawsuit he had instigated.

There was a constant rehashing of the gambling accusations, with Pete’s version seemingly changing depending on the audience listening. In the modern era, where sports gambling is now not only legal but the money spigot for sports teams, leagues, and sports media alike, cries of hypocrisy rose up. Baseball – rightfully – ignored them, as legal betting wasn’t the problem with Pete Rose. Rose, more than anyone, knew right where the bright red line of “don’t do this” was and crossed it anyway. Gambling got Pete Rose banned, but the truth is it was his jackass behavior personally and publicly that kept him banned. Baseball, like everything else, is a people business, and Pete Rose had a long habit of not treating the people he most needed to believe in Pete Rose particularly well.

By the time adult me finally met Pete Rose in person at a fight in Vegas in 2011, both my youthful fandom and pre-ban Pete were long gone. It was quite the scene, in a venue where you had Floyd Mayweather and his entourage causing mayhem and attention on one end, the ring in the middle, and Pete Rose and his son on the other with a stream of people coming and going to both. Darius McCrary sang the national anthem for the main event while some guy I didn’t know sang “God Save The Queen” for the British fighter. It was like a giant sports culture sandwich with the Family Matters guy singing along. Vegas at its insane, over-the-top best. And McCrary can really sing.

When the folks I was with – because this outing was a gift and way above my sergeant’s pay grade at the time – said “we can go over and meet Pete now,” inside, I really didn’t want to. But I went. Pete was polite enough in that way celebrities go through the motions of knowing they are in public and need to smile and nod while half paying attention do. Sitting in his chair with the rigid white baseball cap he frequently wore and that always looked blunt and odd on his head, he looked old, tired, worn out.

Writers and poets wax on about how time wears you done no matter how famous you are. Thing is, while death is undefeated, aging somewhat gracefully is not a product of battling time and tides but of making good life decisions that don’t hand time and tides easy ways to batter one about. Pete Rose’s legacy as one of the greatest hitters of a professionally pitched baseball the world has ever seen – still one of the hardest sports-related things an athlete can aspire to do – aged poorly because Pete Rose the man never could discipline himself in life the way he did at the plate.

There is nothing romantic about this. Pete Rose doesn’t owe any fans anything. Fandom is a projection we put upon the players to create a personal connection where there otherwise wouldn’t be because we want there to be one. When I was a kid, I loved baseball and loved being a Pete Rose fan. I still love baseball, but evidence demands a verdict, and I long ago had an honest reckoning over Pete Rose. I believe Pete Rose when he says he loved baseball; I just wish Pete Rose had loved himself enough to reign in his worst impulses. Love without the discipline to control ourselves quickly becomes an excuse to do all sorts of things that are known to be wrong but get justified by uncontrolled passion.

There is this line folks throw out that Pete Rose loved baseball even when baseball didn’t love him back. But that isn’t true. Baseball loved that Pete Rose who was Charlie Hustle, who played hard, who lived for the split second when wood met bat and magic happened on the field. Baseball mythologized that Pete Rose. The tearing down of the legend wasn’t by baseball; it was by Pete Rose, the hit king who just never learned how to stop hitting himself with self-inflicted wounds.

Trying to love someone like that isn’t possible without it becoming abusive, since if you truly feel for them, it turns to a needed separation and feelings of pity, sadness, and a historic amount of “what might have been.” None of which can be fixed with hustle. Perhaps Pete Rose will now find the peace that he seemed to be searching and lacking on this side of eternity. The boy who was a Pete Rose fan is mourning and sad, and as a grown man I think this is a good time to give all the other stuff that came with Pete Rose a rest.

With Rose I choose to remember the story told of him coming to the plate during the amazing 1975 World Series, with the verdict very much in doubt, and marveling to Carlton Fisk, “This is a helluva game, ain’t it?”