The D-Day That Never Was

On June 5th, 1944, Supreme Allied Commander Dwight Eisenhower penned a letter that, thankful, was not need after the success of D-Day on June 6th, 1944.

This piece was originally for the 75th anniversary in 2019, and I re-up here on the eve of the 80th anniversary

With the 75th anniversary of the D-Day landings in Normandy that marked the beginning of the end of WW2, plenty of attention will be paid to what happened in the stormy gloom of that morning. There will be stories told of unimaginable bravery from the allied troops who, despite so much going wrong, fought and clawed that first foothold onto the continent oppressed by the Nazis. Memorials like the vast cemetery above the beaches will be adorned and visited with hushed and reverent tones. World leaders will gather where once fierce fighting took place and give speeches in the places where the din of battle once shattered the shoreline.

An estimated 300 living veterans will be in attendance, the shockingly dwindled remnants of a generation that — having saved the world — have now nearly passed from it. Modern troops dressed as their forerunners climb Pointe Du Hoc and parachute into the fields, not to heavy enemy fire but the applause and delight of adoring crowds. All the world pauses to remember, and to be thankful, and to celebrate a time when the fate of the world really did hang in the balance.

But the man who gave the order to go for H-Hour on D-Day was all too aware of how the whole affair rested on a knife’s edge that could very well have gone the other way. Like other warrior heroes in history, Dwight D. Eisenhower is more marble statue and list of accomplishments than living man to the modern memory. The Supreme Allied Commander agonized for days, fighting with not only the weight of command and the horrid weather, but the machinery of keeping the greatest armada the world had ever seen ready for battle and focused on the task at hand.

Ike would later be criticized in his own country as president as being rather boring and an unflashy speaker, especially contrasted to his successor in the White House, John F. Kennedy. But the man could write, proven by not only his personal papers but the fact that he wrote his own comprehensive volume on the crusade in Europe in two months and without any ghost writers. So fitting it was a piece of paper that had his own handwriting on it that might be the most telling thing he ever wrote.

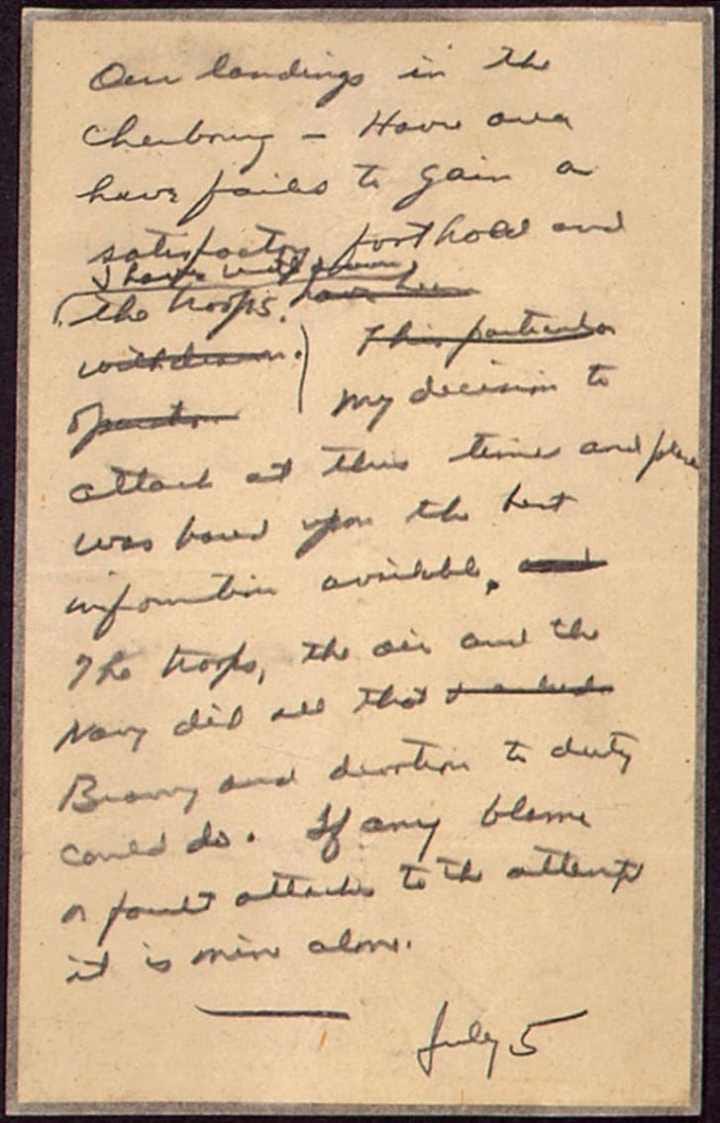

Our landings in the Cherbourg-Havre area have failed to gain a satisfactory foothold and I have withdrawn the troops. My decision to attack at this time and place was based on the best information available. The troops, the air and the Navy did all that bravery and devotion to duty could do. If any blame or fault attaches to the attempt it is mine alone.

It is an astounding thing to read. In what we now know as one of the greatest triumphs in not just military but human history, Eisenhower felt the full weight of potential failure. Tellingly, he scratched out “have been withdrawn” to “I have withdrawn”.

It is not an insignificant a change.

Chiefly it shows leadership, of Eisenhower the consummate soldier taking the full burden of the failure, shielding his troops from blame as a good commander should. But it was much more than that. In taking the full blame personally, he was laying the groundwork for the next attempt. And he knew if Overlord failed, there would be another attempt. The argument could be made that, this time, it will work because that fool Eisenhower isn’t in charge, this time. This time, it would work.

That sentiment was inlaid into FDR’s “Mighty Endeavor” prayer that he gave to the nation on radio, which for the common American was the first notice that the liberation of Europe was finally underway. While the fighting was still going, the possibility of temporary failure that Eisenhower prepared for was also on the president’s mind. But Roosevelt made it clear the resolve was to win in the end regardless, not just because of strategy but because good must prevail over evil.

Their road will be long and hard. For the enemy is strong. He may hurl back our forces. Success may not come with rushing speed, but we shall return again and again; and we know that by Thy grace, and by the righteousness of our cause, our sons will triumph.

They will be sore tried, by night and by day, without rest-until the victory is won. The darkness will be rent by noise and flame. Men’s souls will be shaken with the violences of war.

For these men are lately drawn from the ways of peace. They fight not for the lust of conquest. They fight to end conquest. They fight to liberate. They fight to let justice arise, and tolerance and good will among all Thy people. They yearn but for the end of battle, for their return to the haven of home.

Some will never return.

Had D-Day failed and another attempt been necessary, historians postulate that such a task would have taken perhaps another year, and who knows how many more lives. And thankfully we never found out. The allied troops carried the day, tenaciously grabbed their foothold on fortress Europe and relentlessly drove for the conclusion of the war nearly a year later. The actual wording and setting that Eisenhower gave to launch Operation Overlord is disputed. Ike himself wrote at least 5 different versions of what he said, and how and where he said it. But in the hours after giving the order, in the almost full day it took to implement and put troops on the beach, he took up his pen and wrote the note that would thankfully never be needed.

The humanity of Eisenhower in those moments of doubt should dovetail with understanding that the veterans and honored dead of the Great Crusade were not great because they were supermen, but men who resolved to succeed and thus became great. In our praise we should pause to understand it could have been very different, if not for innumerable acts of courage over thousands of places and scores of times, most that we will never know. In Eisenhower’s letter taking the blame for the D-Day that never was, we have another thing to be thankful for to the last of the greatest generation before they pass. The men, from the Supreme Commander all the way to the privates, were well aware the challenge, were daunted by the task at hand, knew it was a clearly present evil they were fighting against…and totaling it all in their minds collectively and individually answered the way Ike did to his staff when the opening presented itself to launch the invasion:

“OK, We’ll go.”

What Ike wrote about walking the beach after the fact..”Nowhere could one step..” without stepping on remains..